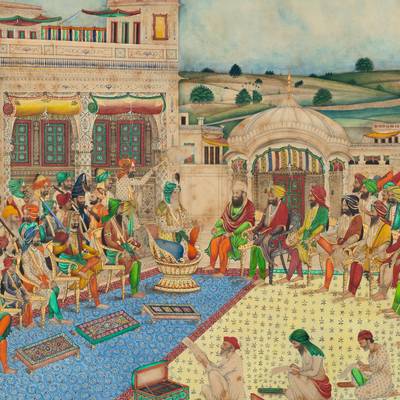

Lahore Durbar by Gurbaksh Matharu

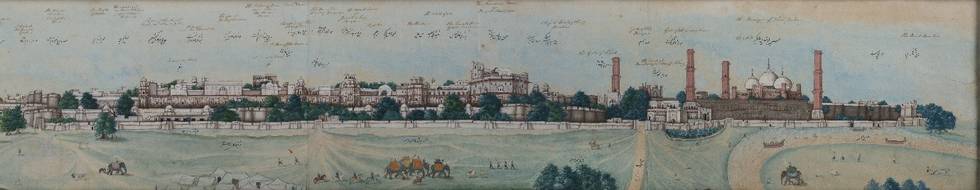

As a capital city, Lahore provided an unrivalled strategic and economic position. Its connection to trade routes linking Central Asia to the rest of the Indian subcontinent was an important practical advantage, while its prestige as a former capital of the Mughal Empire – now under Sikh rule – offered a perfect sense of grandeur.

The Lahore Fort had been constructed by the third Mughal Emperor, Akbar, in the late 16th century. One of Ranjit Singh’s (1780-1839) first projects after capturing the city in 1799, was an enhancement of the structure, which would serve as the new setting for his court or durbar.

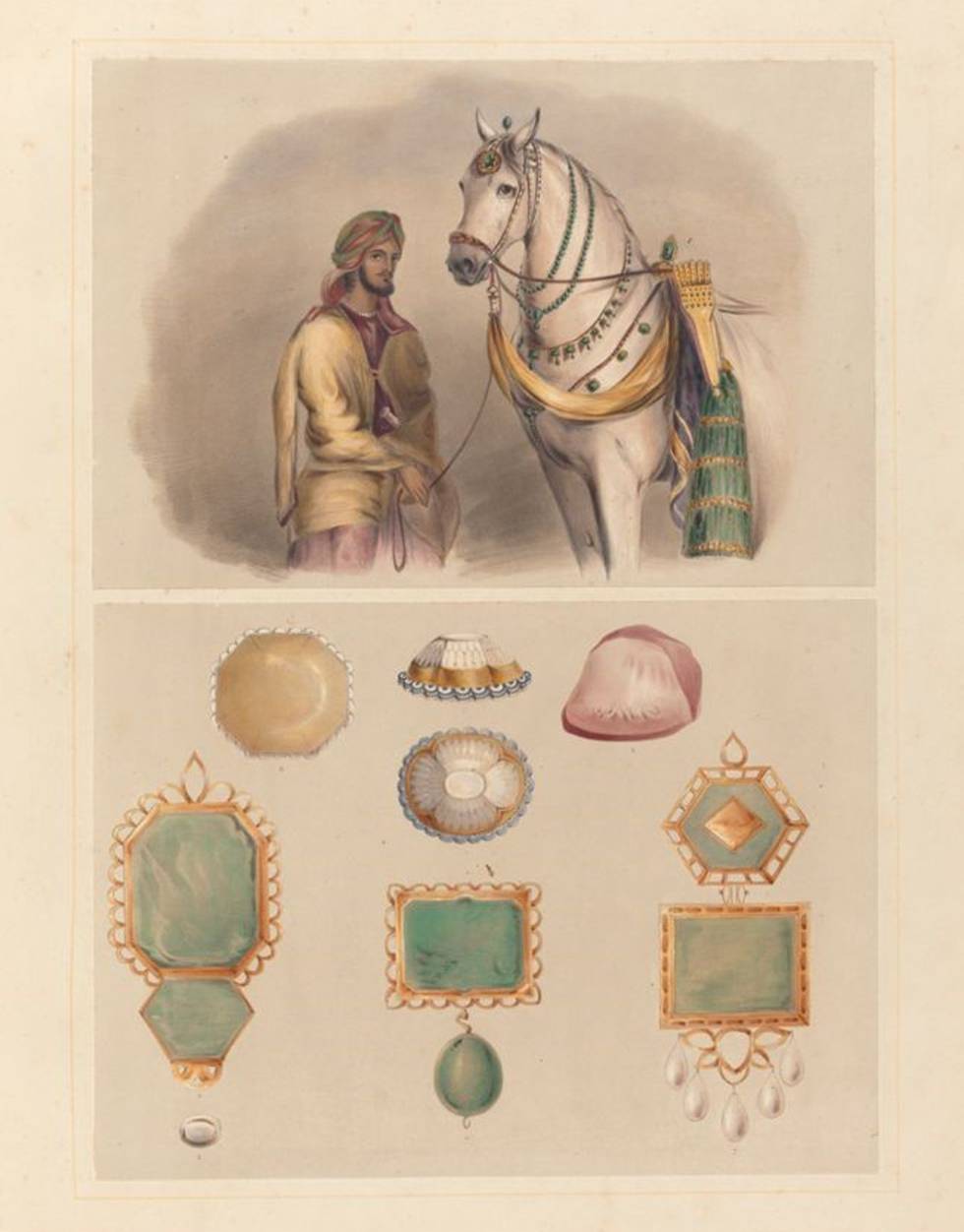

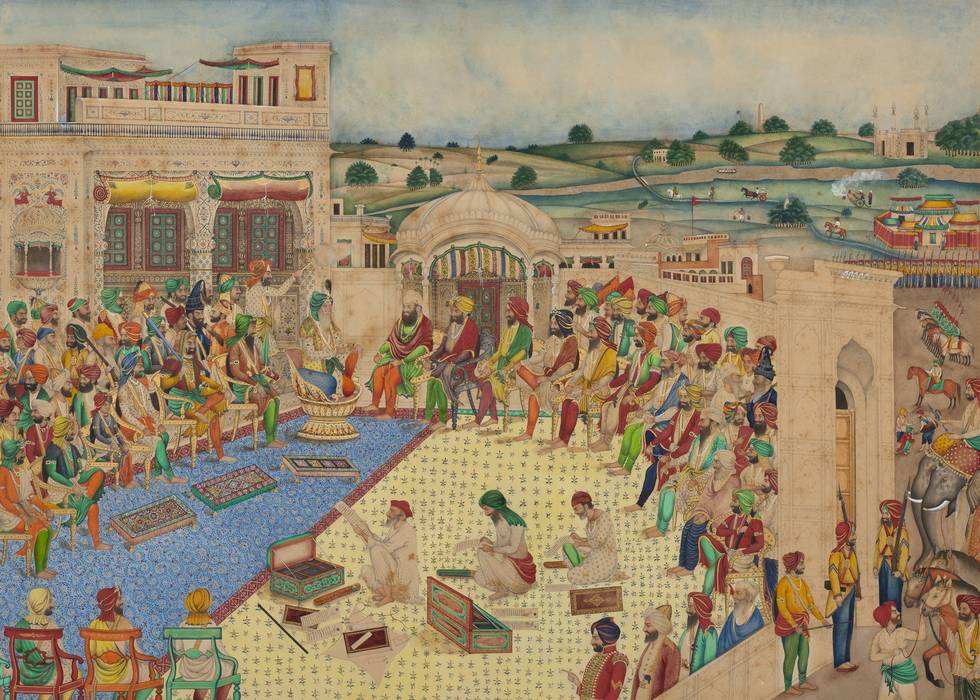

Paintings produced around the time of Ranjit Singh’s reign offer a glimpse into the splendour of his court. State occasions were designed to showcase the prosperity of the kingdom, every detail brimming with luxury – even down to the horses, whose harnesses were set with emeralds.

The decorative arts of the court played a key role in diplomacy. Chronicles record the numerous instances of textiles, jewellery and weapons being presented not only to distinguished guests, but also to Ranjit Singh’s courtiers and generals. Horses and elephants, with gold saddles and seats, were also offered. Such gifts were part and parcel of courtly ceremony. Key to the display of kingship at Lahore, and throughout South Asia, was the presentation of ‘robes of honour’ or khil’at. These consisted of a set of garments, sometimes also including jewellery or ornate weapons, which were presented by the ruler as a mark of distinction. These ceremonies displayed the prosperity and generosity of the ruler, acted as an acknowledgement of status or allegiance, and enacted the hierarchy between a ruler and his subject.

Central to such gift-giving practices was the Lahore Treasury or toshakhana, which supplied the needs of the court. Textiles, jewels, decorative arts and arms and armour could all be readily sourced from the treasury, which was both a repository and a specialist centre of production. A range of craftsmen were employed, all under the supervision of Misr Beli Ram, who had the important task of selecting gifts that befitted the specific ranks of their intended recipients.

While the Lahore Fort was the official setting for Ranjit Singh’s durbar – his court was a travelling one. Whether for hunting, religious occasions, diplomatic meetings, warfare or the general administration of his kingdom, the court moved with its emperor.

In these situations, a durbar tent could easily be constructed to the standards befitting royal ceremony. A visitor to one such temporary structure reported that it was made entirely of luxurious shawls, which also covered the floor.

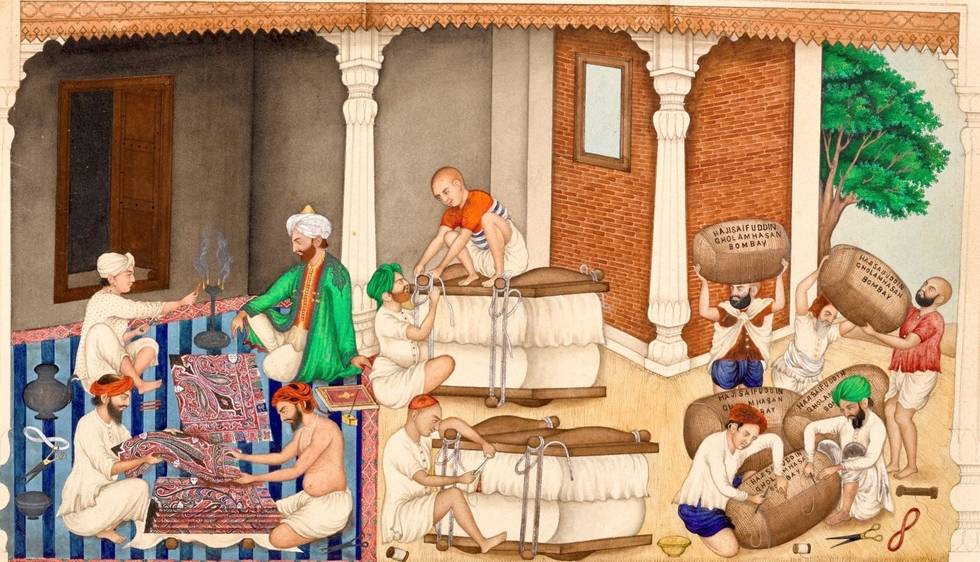

The peripatetic nature of the court is reflected in the design of Ranjit Singh’s golden throne, which includes four handles at its base. Covered in sheets of gold and fashioned by the goldsmith Hafez Muhammad Multani, the throne is likely the most iconic symbol to survive from the Sikh kingdom. As a visual statement of wealth, it is also a testament to the flourishing trade of the region. The ample gold used in its production was likely earned in exchange for Punjab’s many exports, which included salt, indigo, silk, saffron, fruits, and one of its most sought-after products: the Kashmir shawl.

A single shawl could take upwards of 18 months to produce and was prized internationally. The trade attracted global merchants from China, Central Asia, Iran, Turkey, Britain and France, who procured shawls in styles adapted to their own markets.

The wealth of Lahore – and its affluent courtiers – lured artists and artisans from across the empire and beyond. Painters such as Kehar Singh and Imam Bakhsh Lahori were heavily patronised, with the latter being a favourite amongst Ranjit Singh’s French generals. This period saw the construction of new havelis, or mansions, many of which were embellished with wall murals. Music and dance also thrived, often gracing the halls of the royal court. This burgeoning prosperity extended across the Sikh Empire, with cities like Amritsar, Srinagar and Sialkot being well-known centres of art and craftsmanship.

Artistic production continued following Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839. For instance, his second-eldest son, Sher Singh, welcomed the Hungarian oil painter August Schoefft to his court, whom he commissioned royal portraits from. After the annexation of Punjab by the British East India Company, some artists adapted their styles to suit the new British elites, while others found refuge in the smaller Sikh princely states located south of the Sutlej river, such as the court of Patiala.