The Venus Series

Please drag left or right to view the scenes.

Date: c. 1754

Materials: Oil on canvas

Measurements: 164.5 x 71.5 cm, 164 x 71 cm, 164 x 76.6 cm

Inv. Nos: P429, P438, P444

In Venus and Vulcan, Francois Boucher depicts Venus with her husband, Vulcan, the god of fire, smithing, and armor. The scene takes place in Vulcan's forge, where Cupid sharpens his arrows on Vulcan’s anvil while the god, captivated by Venus, is momentarily distracted.

Venus, not always on good terms with her husband, seduces him here to persuade him to forge weapons for her mortal son, Aeneas. The second scene, Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, shows Vulcan learning of Venus’s affair with Mars, the god of war. Vulcan crafts a golden net to trap the lovers and, after capturing them together, invites the other gods to witness their humiliation.

In The Judgment of Paris, the shepherd Paris is bribed with the promise of possessing the world’s most beautiful woman. He awards the golden apple inscribed "to the fairest" to Venus rather than to Minerva, goddess of wisdom, or Juno, queen of the gods.

Since the Renaissance, artists have identified with Paris’s choice among rival forms of beauty, relishing the chance to depict three distinct female nudes, thereby inviting viewers to make similar aesthetic judgments.

This subject encapsulates Francois Boucher’s (1703-1770) artistic interests and serves as the central panel in a series in the Wallace Collection that celebrates Venus and the allure of visual beauty.

In The Judgement of Paris, a sinuous chain of figures begins with Paris seated on the ground in a leopard skin, moves to Venus resting on clouds and shown frontally to highlight her beauty, then to a teasing back view of Minerva, and finally to the discontented Juno positioned above.

The cloud formations in the other two canvases suggest that Vulcan’s discovery of Venus with Mars would have been positioned to the left of Paris, with Venus persuading Vulcan to forge weapons for Aeneas on the right.

These two canvases emphasize Venus and her lovers, featuring Boucher’s luscious, pearly female forms offset by the bronzed figures of Mars and Vulcan, who appear strikingly similar, likely because the same model, Deschamps, posed for both.

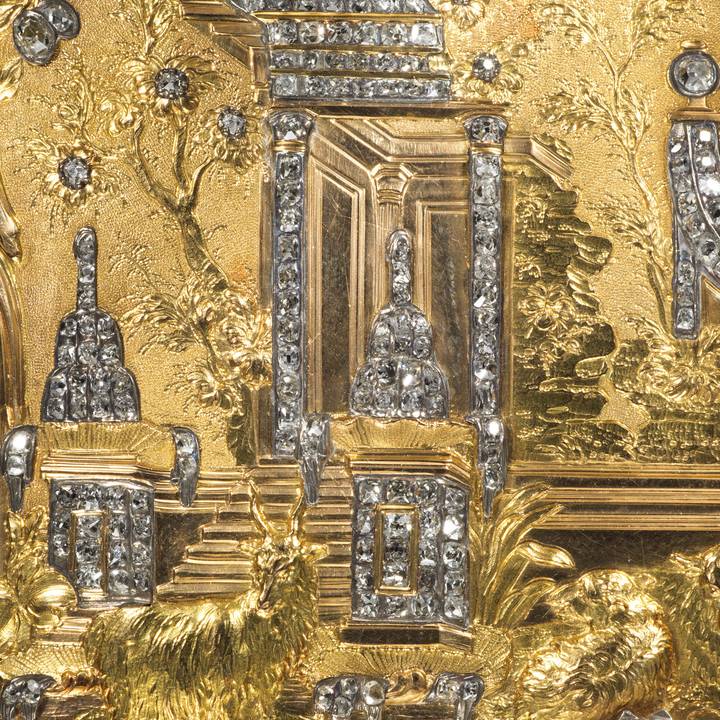

Beyond the sensual depiction of figures, Boucher’s canvases delight in finely painted details.

In Mars and Venus, he carefully differentiates between blue velvet, peach-striped silk taffeta, white satin sheets, and the delicate transparent veil in Venus’s hair, while putti, flowers, and abandoned weapons add visual interest around the bed.

Similarly, in Venus and Vulcan, after the viewer’s gaze settles on Venus, slimmed through careful touch-ups, attention shifts to intricate details like Aeneas’s weapons and the realistically rendered anvil and vise.

Both canvases highlight Venus’s sensual allure, but Boucher diffuses potential accusations of obscenity with humor: Mars, for example, wears a comical bow in his hair, alluding to Hercules’s submission to Omphale, while Vulcan’s usual Cyclops assistants are replaced with cherubic Amours industriously crafting weapons of love instead of war.

While these works are decorative, their vertical format implies they were meant to be placed in wall paneling at eye level, demanding more careful execution than an overdoor painting. Their quality, subject matter, and date (1754) later linked them to Madame de Pompadour, though there’s no direct evidence she commissioned them.

Their original location is unknown, but they were later enlarged to match the slightly wider Cupid a Captive and combined to form a screen.

Text adapted from Hedley, J., Francois Boucher: Seductive Visions, London, 2004.