François Boucher’s (1703–1770) activity as a theatre designer is a fascinating aspect of his prolific and varied career. Unfortunately, in the ephemeral world 18th-century theatrical performance, where sets and costumes were often re-used, recycled and then discarded, very few objects relating to this area of the artist’s work survive.

A fire at the Hôtel de Ville in Paris in 1871, which destroyed records concerning the city’s theatres, has made matters worse. It is known Boucher designed productions for the Académie Royale de Musique (the Opéra) in Paris between 1737–39 and 1744–48, and there are accounts of his becoming the Académie’s artistic director between 1761–66.

Records state that he regularly designed for the musical entertainments performed by the Opéra Comique between 1743 and 1754. But only a few sketches for Boucher’s productions survive.

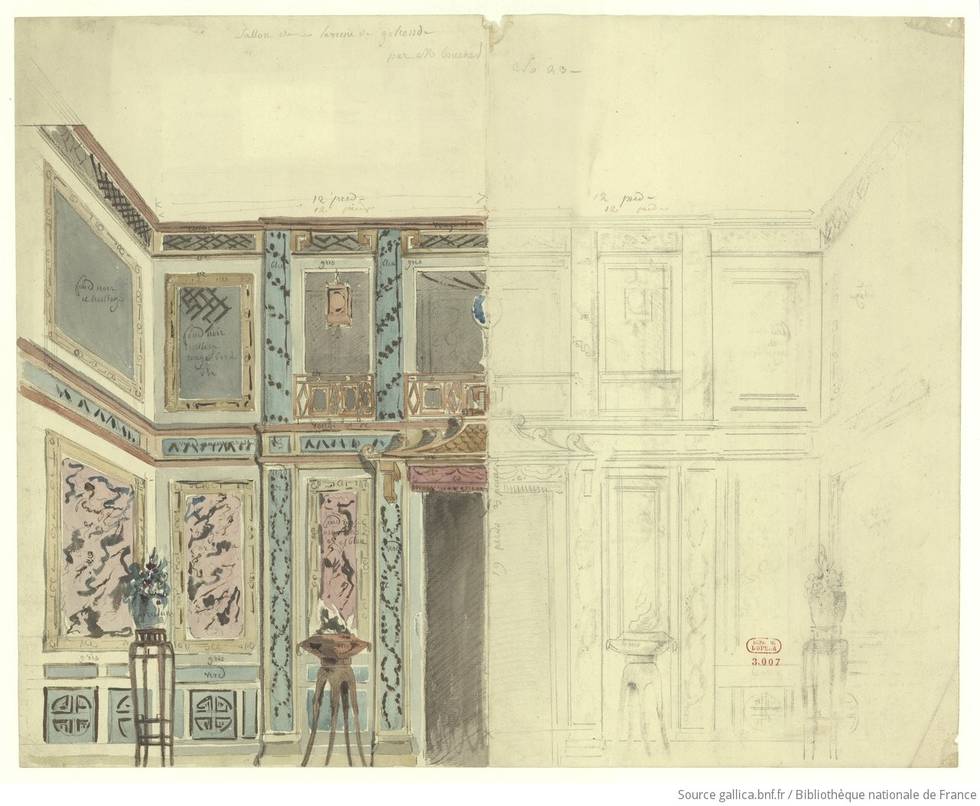

Among them is a late-career design for a ‘Sallon Indienne’ in the first production of a sentimental love tale set in India, Aline, reine de Golconde (Aline, Queen of Golconda), 1766, by Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny (1729–1817).

Boucher’s drawing includes colour notes and measurements for the set-builders. The opera was performed at the Salle des machines, so called because of its elaborate stage machinery, in the former Tuileries Palace in Paris.

An earlier oil painting by Boucher, however, gives us an insight into innovations he may well might have brought to French theatrical productions. The work, which is dated 1741, is thought to depict his design for a revival of the late 17th-century opera, Issé, by André Cardinal Destouches (1672–1749).

If this assumption is correct, the setting shows a distinct move away from the more formal and rigidly perspectival stage designs that previously held sway in Paris. Instead of a clear central space in which the performers would face the audience, Boucher’s pastoral landscape evokes a relaxed yet Arcadian world of tumbledown charm.

The success of entertainments on pastoral themes at the time, as well as Boucher’s probable contributions to the genre, is underscored by the fact that Boucher’s illustrious patron Madame de Pompadour (1721-1746), mistress-in-chief to Louis XV, performed the role of the nymph Issé in a 1749 production staged in the court theatre built at Palace of Versailles. Rather frustratingly, it is not known if Boucher was involved.

What is known is that many stage productions on a pastoral theme seem to have directly fed into the way Boucher constructed his pastoral paintings. When looking at Boucher’s two 1749 pastoral masterpieces in the Wallace Collection, for example, there is a sense of theatricality, with figures and animals playacting within an idealised and relaxed – yet carefully constructed – space in which the receding landscape elements overlap like stage flats.

Boucher’s pictures also appear to include a similar repertoire of elements as his design for Issé, with rustic buildings, tumbledown stables, overgrown carvings, fountains and distant hill-top villas.

The links between the theatre and Boucher’s work as a painter, printmaker and designer for the decorative arts, extended beyond their stage-like settings, however. A number of his pastoral figures have a strong relationship to theatrical productions in which he may have been involved.

For example, the characters in the comic pantomime Vendages de Tempé (The Harvest in the Vale of Tempé) written and first staged in 1745 by Boucher’s friend Charles-Simon Favart (1710–1792), often appear in Boucher’s art.

Lisette the pretty shepherdess from the show, her sister, the disapproving Babette, Lisette’s suitor, the ‘Little Shepherd’ and the comical child shepherd Celadon repeatedly feature as themselves, or in adapted form, in Boucher’s paintings as well as in the tapestries and on the porcelain inspired by his designs.

The scenes and gestures many of Boucher’s pastoral figures enact may also have a strong relationship to theatrical productions. Among the most memorable scenes of Favart’s pantomime and its later adaptations, is the moment when the Little Shepherd teaches Lisette to play the flute. Another is where he feeds her grapes.

The playful eroticism of both would not have been lost on Boucher’s contemporaries, who may well have found it charming as well as somewhat risqué. Indeed, the old French titles given to the Wallace paintings, Les raisins. Pensent-ils au raisin? (‘The Grapes. Are they thinking of the grapes?’) and La Couronne accordée au berger (‘The Crown rewarded to the Shepherd’), were interpreted at the time as having erotic overtones.

Interestingly, in the original Paris stage performance of Les vendages de Tempé the Little Shepherd was played ‘en travesti’ (as a man) by Favart’s wife, the dancer, singer, composer and collaborator, Marie Justine Benoit Favart (1727–1772).

The feminine appearance of Boucher’s Little Shepherd type – as in Pastoral with a bagpipe player – could in part be in recognition of such roles being played by actresses rather than young men.

Of greater impact on Boucher’s painting may be an important reform ‘La Favart’, as Justine Favart was known, introduced to the Opéra Comique costumes. She introduced a relaxed, if idealised and highly colourful, form of rural dress to the stage.

This included the actors wearing clogs or going barefoot, and also the copious quantities of ribbons and pretty fabrics. It would be hard to imagine Boucher’s pastorals without these touches.