Fall-front desk (F300)

Date: 1780

Maker: Cabinetwork by Jean-Henri Riesener; model designed by Jean-François Oeben

Materials: Oak, purplewood, satiné, tulipwood, stained woods, burr wood, ebony or ebonised wood, box, gilt bronze, Carrara marble

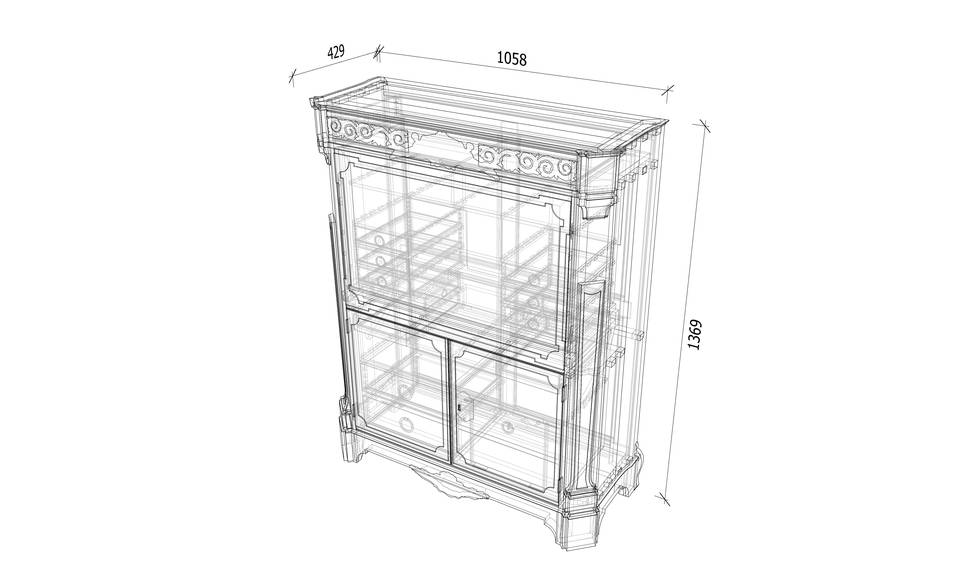

Measurements: 144 x 112 x 45.5 cm

Inv. no. F300

This desk has one of the most illustrious backgrounds of all the Riesener furniture in the Wallace Collection. It was delivered for Marie-Antoinette on 8 July 1780, for use in her private apartments at Versailles. She kept it in her cabinet intérieur (private sitting room) which had recently been redecorated with new curtains and wall-panels, and matching upholstery for a suite of new chairs made by the royal supplier François II Foliot (1748–1839).

The colour scheme was a cool classical white: the textiles were of white silk, woven in Lyon, partly brocaded and partly embroidered with colourful arabesques, flowers and medallions, at a total cost of approximately 100,000 livres. Riesener’s desk probably cost between 8–9,000 livres, itself an enormous amount for a piece of furniture.

Visually the desk is striking. The combination of panels of highly complex pictorial marquetry and neoclassical gilt-bronze mounts make this a statement piece. The colours have faded over the years, and not only would the flowers and motifs have been much more vividly coloured but the sycamore background on which they have been inlaid would have been silvery, in a highly polished finish that was known as satiné gris, or satin grey, and which referenced the sheen of satin. This would have lent itself very well to a neoclassical interior.

The panel at the top incorporates marquetry motifs combined into a trophy, including a caduceus (the attribute of Mercury, the messenger of the gods), a laurel wreath (denoting victory, or glory) and a cockerel, the symbol of France. Below are bunches of flowers in two marquetry vases which were described in the accounts as looking like jasper, a highly polished hardstone that was prized by collectors of neoclassical art.

The mounts further this classical theme, with two male busts supporting the marble at the top of the front corners, and a frieze imitating architectural ornament. The central mount is a mask of Hercules, a classical hero who succeeded by constantly striving and thus a suitable allegory for hard work and study.

Despite the extraordinarily skillful marquetry and the high cost of the desk, it does not seem to have met with Marie-Antoinette’s full approval, and it was moved out of her room soon after its delivery.

Riesener supplied another desk less than six months later, which was more to her taste: it was decorated with the mosaic marquetry found on the chest-of-drawers in the room and allegorical marquetry scenes denoting Poetry and Literature, which must have seemed more appropriate for the queen’s occupations.

It is tempting to think that, rather than taking a dislike to Riesener’s first desk, it had always been planned as a stopgap for the room whilst Riesener worked on a new model for her. The first desk was indeed an old model, which Riesener had made before, as recently as 1777 for Louis XVI himself.

This desk was sent to store, but a few years later resurfaced in the king’s apartments at the smaller Château de Saint-Cloud, a more private residence that had recently been acquired by Louis XVI for Marie-Antoinette.

This is perhaps a surprising example of the recycling of royal furniture but, despite the seeming extravagance of some items of expenditure for the royal palaces, the furniture administration did re-use pieces in different furnishing schemes. Moreover, the delivery of a similar desk for the king a few years earlier shows that he clearly found this model and its decoration attractive.

Perhaps because of regular use, this desk required some new restoration and new gilding just before the French Revolution. This was carried out by the new royal supplier, Guillaume Beneman, who had replaced Riesener, and this accounts for the interesting marks on the desk: it is stamped not only by Riesener, as was customary for the maker, but also by Beneman who clearly left his mark after carrying out the restoration.

During the Revolution, the desk was seized by officials from the new administration. They were unable to find the key, so carefully slid the backboard out to allow the contents to be inspected from behind. This illustrates one of the characteristic features of Riesener’s construction methods: almost all the backboards in his fall-front desks and even chests-of-drawers share this design feature. Perhaps the prime reason for making furniture in this way is to allow several different craftspeople to work on the same piece of furniture at the same time, thus allowing the workshop to produce more pieces more quickly. For Riesener, who had to produce an enormous amount of furniture for the royal households, such business practice made sense.

For more information: Jacobsen, H. et al., Jean-Henri Riesener. Cabinetmaker to Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Furniture in the Wallace Collection, Royal Collection and Waddesdon Manor, London, 2020, no. 16.