Date: 1782

Maker: Cabinetwork by Jean-Henri Riesener; mounts gilded by François Rémond; re-veneered (probably about 1795–1815)

Materials: Oak, mahogany, purplewood, ebony or ebonised wood, box, gilt bronze, brocatello marble

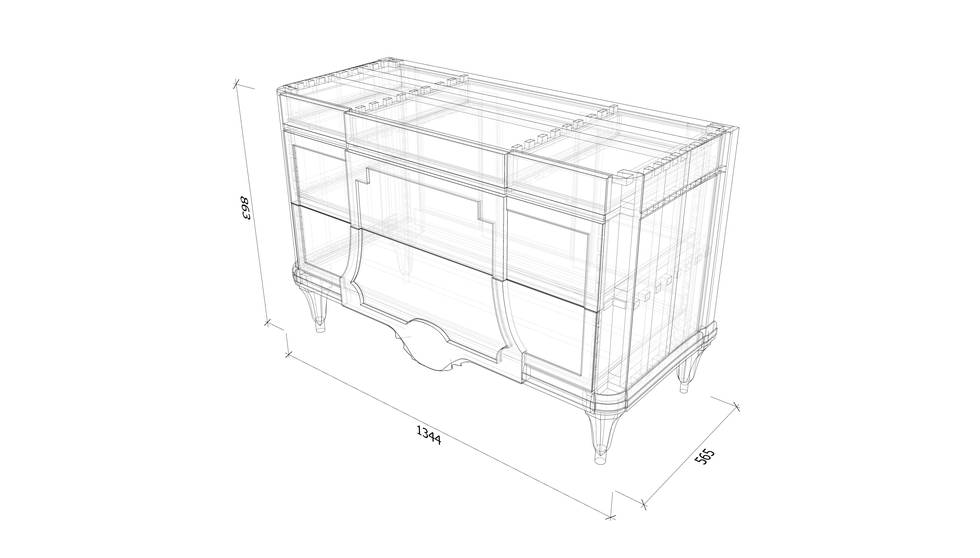

Measurements: 88.5 x 136.3 x 60.2 cm

Inv. no. F248

This chest-of-drawers bears witness to changing tastes and the events of the French Revolution. In the winter of 1780, Marie-Antoinette ordered major changes to her private apartments at the Château de Marly. This had been built in the 17th century by Louis XIV (1638–1715) as a retreat from the strict court etiquette that was in place at Versailles and although it was not used so much in the 18th century, it remained an escape for the royal family.

Marie-Antoinette’s rooms had not been modernised for several decades and were still furnished as they had been laid out for Marie Leszczyńska, the previous queen of France. Marie-Antoinette ordered significant changes, including the remodelling of three mezzanine rooms and redecoration throughout. Riesener was commissioned to make the furniture.

The following spring these three new rooms were finished. Riesener delivered a marquetry chest-of-drawers with a pastoral trophy (in the Musée du Louvre), a writing table (in the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum) and a chiffonnière (a different, smaller type of writing table, now in a private collection).

The chest-of-drawers was also decorated with the customary lozenge marquetry and the new model of gilt-bronze frieze with the queen’s initials in the centre that had decorated the previous chest-of-drawers Riesener had delivered for her at Versailles.

This was clearly a model of furniture that appealed to her, as the next year, in spring 1782, two more similar chests-of-drawers were delivered for her bedroom and its adjacent sitting room at Marly. These two were described as being ‘the same’.

Before they were delivered, Riesener had sent them to the gilder, François Rémond (1747–1812), whom Riesener used for some of his most exquisite royal furniture, where the mounts were gilded in ‘matt gold’. This was an expensive process which brought out the depth of the bronzes and highlighted matt and burnished areas, giving extra life and sparkle to the mounts. By 1788, both chests-of-drawers were inventoried in the queen’s bedroom, valued at the very high sum of 10,000 livres.

Although she did not visit Marly often, Marie-Antoinette’s newly decorated bedroom must have been extremely elegant. She had two paintings over the doors, allegories of Sleep and Awakening, chairs richly carved with ribbons, flowers and laurel leaves by François II Foliot, and a new bed, of a model known as a ‘lit à la duchesse’, a confection of blue silk, feathers and tassels.

The walls and the seat furniture were painted an elegant white at the queen’s express wish; Riesener’s two chests-of-drawers must have looked sumptuous against the simple background. Despite all this activity, the queen was only to spend one week in her new apartments before the Revolution.

In 1793, after the king and queen had been executed, the furniture at Marly was taken off to be sold for the state. One of these three chests-of-drawers, however, was retained, no doubt a recognition on behalf of the Revolutionary administration of their status as works of art to be preserved.

The Wallace Collection chest-of-drawers was sold, and was separated from its pair. At some stage, probably during the next 20 years, Riesener’s original marquetry was stripped from the chest-of-drawers and replaced with the beautifully figured plain mahogany veneer that we can see now.

The marquetry was considered old fashioned, and its characteristic lozenge pattern was associated with the royal family for whom it was made, making it very unpopular. Instead, the new veneer spoke to the more modern taste for plain woods. Fortunately, however, the gilt-bronze mounts were kept and replaced on the newly veneered mahogany.

Inside the drawers, it is possible to see where the original mount fixings would have been for the gilt-bronze frame that once held the marquetry trophy in place. It is very likely that when the mahogany veneer replaced the original decoration, whoever did the work kept the marquetry trophy, perhaps planning to use it at a later date.

A recently discovered marquetry panel in a museum store may provide the missing link to this story. Its dimensions fit where the fixings are on the chest-of-drawers, and the trophy depicted in marquetry is exactly the same as that on the other Marly bedroom chest-of-drawers now at Versailles. It is mounted on a backing, which would have allowed it to be shown as a work of art in its own right. This underlines not only how tastes change, but also how highly regarded Riesener’s marquetry has been ever since it was made.

For more information: Jacobsen, H. et al., Jean-Henri Riesener. Cabinetmaker to Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Furniture in the Wallace Collection, Royal Collection and Waddesdon Manor, London, 2020, no. 21.