During the 18th century, Paris was at the centre of European luxury goods production.

Wealthy aristocrats and the court promoted fashions in architecture and furniture, and royal patronage played an important role in stimulating styles. Architects, designers and craftspeople worked (often together) to realise grand decorative schemes, in which cabinetmakers played an important role.

When Riesener arrived in Paris in the 1750s, cabinetmaking was a competitive but highly regulated craft, governed by a guild. In order to become a cabinetmaker, a lengthy training was involved, which typically involved progression from apprentice, to journeyman and finally to master.

On the submission of a successful masterpiece, and the payment of guild fees, a journeyman could qualify as a master and had the right to run his own workshop and stamp his furniture with an identifying mark.

Riesener entered the workshop of Jean-François Oeben (1721–1763), an accredited supplier of furniture to the Louis XV (1710–1774), as a journeyman and worked alongside at least two others, Oeben’s brother Simon-François (about 1722–1786) and Jean-François Leleu (1729–1807).

After their master died, there was competition between Leleu and Riesener for ownership of the workshop. This was typical in the 18th century and was seen as a way of gaining ownership of an established workshop with a prestigious client list.

Despite a bitter (and sometimes violent) rivalry between Riesener and Leleu, Riesener gained control of the workshop after marrying Oeben’s widow but continued to use his master’s stamp until he himself became a master in 1767 and started using his own stamp – ‘J ⧫ H ⧫ RIESENER’.

Both Leleu and Simon Oeben went on to establish their own workshops, but neither reached the level of accomplishment and prestige of Riesener.

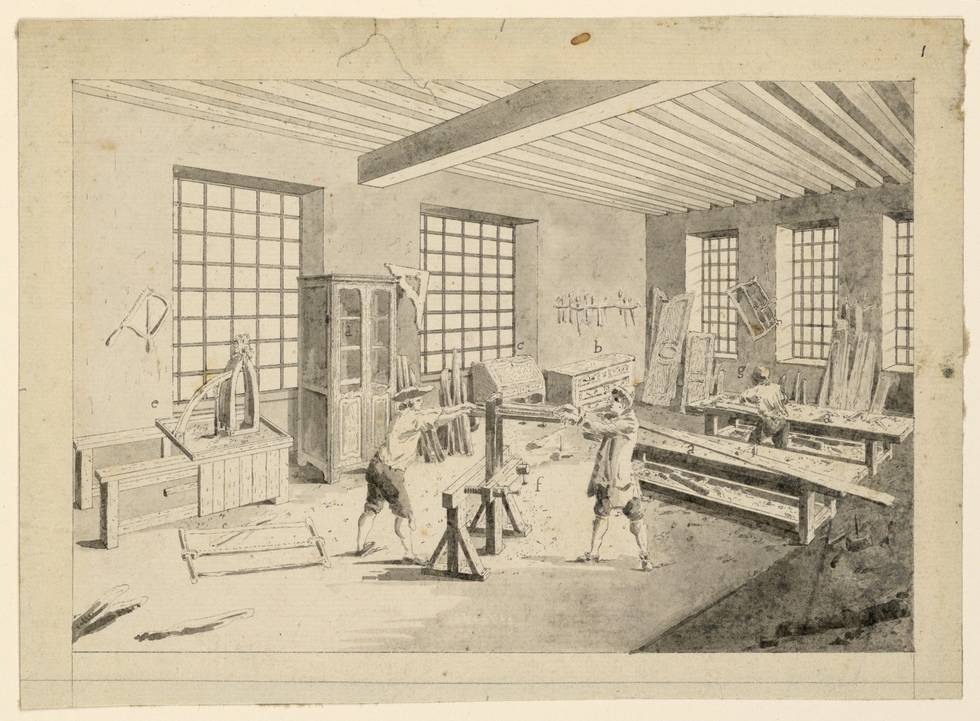

Although furniture-making at this time was very much focused on the master cabinetmaker, it was in fact a collaborative process, which involved craftspeople with a range of skillsets. A workshop would have been a hive of activity, buzzing with people working on all aspects of furniture, from carcases to marquetry.

Strict guild regulations restricted cabinetmaking workshops to producing just the wooden parts of furniture, so they had to call on other craftspeople, like bronze modellers, chasers and gilders, to produce gilt-bronze mounts or locksmiths to produce locks.

Riesener collaborated with a number of bronze workers over the course of his career, most notably the sculptor, chaser and gilder Étienne Martincourt (about 1730–1796).

The apogee of their creative relationship was the comtesse de Provence’s (1753–1810) jewel cabinet, which was delivered in 1787. Riesener created its cabinetwork, whilst Martincourt created the elaborate gilt-bronze mounts. The result has been celebrated as one of the finest examples of 18th-century design.

Riesener’s career, life and success should be viewed within this complex system of competition, patronage and collaboration. These conditions led to intense craft specialisation, in which Riesener thrived and produced exceptional furniture.