Let’s imagine Instagram was available in the 1790s. What might the young Turner’s Instagram feed have looked like? Who would he follow?

Knowing that the hold that the Old Masters had on artistic taste he would seek out accounts dedicated to the work of his European forebears: Claude Lorrain, Titian, Willem Van de Velde, Rembrandt and Canaletto. Celebrated examples of their work were to be found in British collections and from them – or from prints made after them – Turner would adopt ideas for compositions, colouring, classical subjects, dramatic seascapes and bold light effects. He would have also followed the big influencers of eighteenth-century British painting such as Richard Wilson, Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds. Inspired by their painterly innovations and the ways in which they incorporated references to the Old Masters in their work, be it portraiture or landscape, their careers – particularly their status as founder members of the Royal Academy – also forged a new pathway for the education and recognition of British artists in their wake. Another group of influencers entailed an elder generation of landscape watercolourists: Edward Dayes, John Robert Cozens, Paul Sandby (Edinburgh Castle), to name but a few. From these artists Turner learned that a watercolour could have ambition and flair, and that the medium was a vehicle for experimentation as well as money-making, two very attractive prospects for the young Turner.

Turner entered the art world at precisely the moment when watercolour was trending. Coming to be thought of as an exciting medium, it was being celebrated as a particularly British arena of artistic excellence, an important accolade at a time when Britain was at war with France. Watercolourists who depicted British scenes were therefore able to ride a wave of patriotic investment in the home front. Turner would have felt this buzz around the medium. Richard Westall’s watercolours of historical subjects rendered in bold colour dazzled the critics. Paul Sandby, meanwhile, broke landscape watercolour convention by deploying an innovative blend of media on extra-large sheets of paper, framing them like oils to be wall-hung, as opposed to kept in a portfolio. Not long after his death in 1811 Sandby was dubbed ‘the father of modern Landscape Painting in watercolours’. The use of the word ‘painting’ here is important – an acknowledgement that the medium could perform the same kind of ‘high’ art function as oils and that it needn’t be classed as a medium fit only for preparatory, amateur or technical drawing.

Watercolour paintings could now, therefore, be collectors’ items in their own right. Turner and his friend Girtin were fortunate in their employment to copy an array of watercolour landscapes in the collection of Dr Monro, such as British monuments and landmarks by Michael Angelo Rooker and Edward Dayes or John Robert Cozens’ sweeping Italian vistas (Lake Nemi). This experience no doubt cemented Turner’s skills, inspiration and keenness to assimilate himself into this lively, experimental and commercially promising field. Assimilate and innovate he did, going on to be recognised, with Girtin, in the early 1800s as leader of a new generation of practitioners that would take the medium to new heights. Their work was praised for helping evolve watercolour landscape even further than Sandby had, less reliant on drawn outlines and built, instead, using many layers of thin washes and only occasional use of thicker bodycolour (gouache).

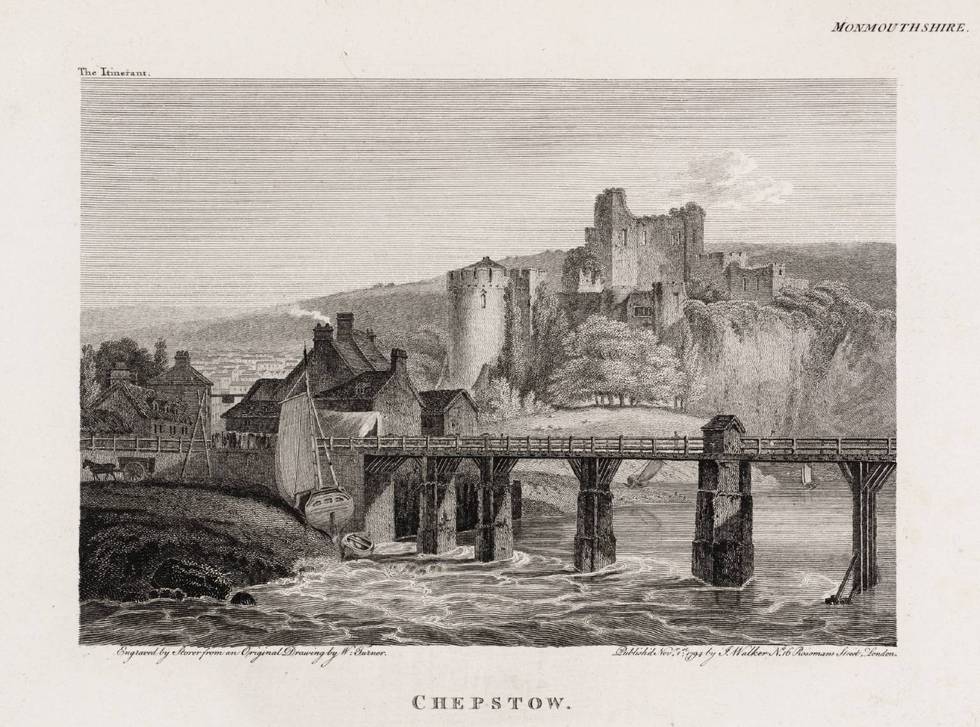

Making watercolour landscapes was a wise choice for an emerging artist. At the very least the materials were cheaper, less cumbersome and faster to work than canvas and oil, and therefore less of a risky investment of time and money. Like so many other practitioners, Turner monetised his skill by teaching pupils and by selling watercolours to print publishers. He had the advantage of arriving on the art scene just as landscape culture was booming. With the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars blocking access to the Continent, Brits became more interested in scenery closer to home. Following guidebooks and step-by-step drawing manuals, tourists engaged with the British landscape like never before while new academic concepts like the Picturesque and the Sublime stimulated discussion about the atmospheric and topographical qualities of places and the feelings they gave rise to. All this activity fuelled the market for landscape images. Selling images to print publishers from the very outset of his career (Chepstow), Turner learned that the value of engaging with print culture was not just financial, but a way to remain relevant to commercial and intellectual trends.

However, there was one barrier that Turner’s skills in watercolour couldn’t break. To be elected a Royal Academician, the status that signified you’d made it as a professional artist, Turner needed to be exhibiting oil paintings. An increasingly large segment of the market for oil paintings in the late eighteenth century dealt in Old Masters. This had a significant impact on contemporary British art, too, since the enthusiasm for Old Master works skewed patrons’ tastes. The competitive nature of Royal Academy exhibitions also impacted the kinds of work made – in a crowded cheek-by-jowl hang artists had to find ways to shine. While portraitists could trade off their A-list sitters, artists working in other genres had to think differently, going bigger, brighter or bolder. French artist Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg (Lake Scene) paved the way for Turner in this regard, painting contemporary subjects in vivid colours and using theatrical effects (indeed de Loutherbourg also undertook stage design work).

Turner’s first exhibit in oil was an astute assimilation of influences and attention-grabbing strategy (Fisherman at Sea). You can see his study of Rembrandt in his depiction of lamplight and moonlight, for example, but these highlights would have also served as interior spotlights, drawing the eyes of the crowd to this moody sea piece.

Turner is credited with a heroic role in the story of British art – the young star, the rebel, the disrupter, the genius whose originality can’t be surpassed. When it came to watercolour, these claims were already being made about him very early on in his career. He marked himself out by using his eye for dramatic composition, experimental techniques and an intellectual ability to imbue greater meaning in landscape, telling stories about places through the use of atmosphere or keenly observed details. Aside from his sheer technical skill, dedication and savvy networking, one of the real keys to his meteoric rise was his ability to survey the field he entered into, appeal to the market, and use the achievements of his fellow artists, past and present, as the springboard to his own.

The names of Paul Sandby, Michael Angelo Rooker and Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg are unlikely to grace the Instagram feeds of anyone beyond the most dedicated followers of late eighteenth-century art. But whenever a Turner pops up online, we can be assured that behind every image of his is something of the inspiration these now lesser-known names provided him in his youth.

This article was written by Dr Amy Concannon, Manton Senior Curator of Historic British Art at Tate.